It’s English… but not as we know it

The fascinating language of the skies…

Every second of every day there are on average between 10,000 to 14,000 commercial flights operating around the world. With this in mind, the safety of each flight is of paramount importance.

Every second of every day there are on average between 10,000 to 14,000 commercial flights operating around the world. With this in mind, the safety of each flight is of paramount importance.

Although air incidents in one year are far less than road traffic accidents around the world in one day, unfortunately, they do happen… often with catastrophic consequences. Statistics have shown that, notwithstanding many are caused by technical faults, the majority are the result of human error – often due to poor communication skills.

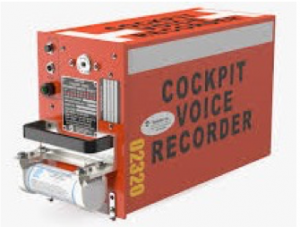

When an incident happens, Air Crash Investigators are interested in discovering its cause. To do this, as well as examining the accident site itself, investigators are interested in the data collected by two very important instruments on-board every commercial aircraft… the “black boxes”.

Black boxes aren’t black at all. Actually they’re orange so that they are visible and easily recoverable. There are two of these “boxes” which record information about the flight. One is the Flight Data Recorder. This instrument records the flight parameters of the aircraft, telling investigators how the aircraft was performing prior to the incident.

Black boxes aren’t black at all. Actually they’re orange so that they are visible and easily recoverable. There are two of these “boxes” which record information about the flight. One is the Flight Data Recorder. This instrument records the flight parameters of the aircraft, telling investigators how the aircraft was performing prior to the incident.

The second of these two recorders is the Cockpit Voice Recorder. It is often this instrument that investigators want to focus their attention on as this records the sounds within the cockpit – in particular, as the name suggests, the voices within the flight deck. This means that the language used by pilots – and Air Traffic Controllers – must be clearly understood by investigators. As a result, a special and unique language is used. This language is known as ICAO Standard

Phraseology in Radio-telephony.. commonly known as Aviation English.

Early years of communication in aviation and radio-telegraphy

For 100 years since mankind started flying, aviation has always looked at how pilots in the air could communicate effectively with people on the ground. Early examples of communication are flags, semaphores, even notes! Yes, notes that would be written on a piece of paper, placed in a “container” with a handle which pilots, in a low pass, would collect using a hook. They would then write a reply and drop it back to the person on the ground… quite a dangerous feat! However, back in December of 1894, an Italian aristocrat from Bologna named Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi, demonstrated the first radio-telegraph communication. Over the years, having moved to the UK, Marconi worked on developing Samuel Morse’s wired telegraph system, using Morse Code – a series of “dots” and “dashes” known as “dits” and “dahs” – into wireless radio-telegraphic communication.

In March, 1897, Marconi transmitted the first wireless Morse Code message over a distance of about 6 km (3.7 mi) across Salisbury Plain. On 13, May, 1897 Marconi sent the first radio-telegraphic message across the sea – 6 km over the Bristol Channel from Flat Holm Island to Lavernock Point in Penarth. That message read “Are you ready” – an appropriate message as this was the start of a revolution in wireless communication.

In March, 1897, Marconi transmitted the first wireless Morse Code message over a distance of about 6 km (3.7 mi) across Salisbury Plain. On 13, May, 1897 Marconi sent the first radio-telegraphic message across the sea – 6 km over the Bristol Channel from Flat Holm Island to Lavernock Point in Penarth. That message read “Are you ready” – an appropriate message as this was the start of a revolution in wireless communication.

Over time the range of Marconi’s radio-telegraph system was increased and, in the 1920s, wireless Morse Code units started to be used in aviation on a regular basis. The first transmitters were bulky and so were only installed on large airships like the Zeppelins The first use of the wireless Morse system in an airplane was in 1928 on a flight from California to Australia on board the “Southern Cross”.

Over time the range of Marconi’s radio-telegraph system was increased and, in the 1920s, wireless Morse Code units started to be used in aviation on a regular basis. The first transmitters were bulky and so were only installed on large airships like the Zeppelins The first use of the wireless Morse system in an airplane was in 1928 on a flight from California to Australia on board the “Southern Cross”.

Radio Operator’s station aboard the

Fokker F.VII Trimotor “Southern Cross”

Entering the era of radio and audio transmissions

It was on 23 December, 1900 that radio communications made a giant leap forward. This became possible thanks to a Canadian-born inventor – Reginald Aubrey Fessenden – who successfully transmitted speech over a distance of 1.6 km (circa 1 mi). By early 1901, Fessenden had increased the range of his transmissions to around 80 km (50 mi). In July 1907, that range had extended to 320 km (200 mi)… the era of wireless communication of speech over radio had begun.

It was on 23 December, 1900 that radio communications made a giant leap forward. This became possible thanks to a Canadian-born inventor – Reginald Aubrey Fessenden – who successfully transmitted speech over a distance of 1.6 km (circa 1 mi). By early 1901, Fessenden had increased the range of his transmissions to around 80 km (50 mi). In July 1907, that range had extended to 320 km (200 mi)… the era of wireless communication of speech over radio had begun.

However, transmitting sound over radio waves required a lot more power than Marconi’s Radio-telegraph, and regulating the radio waves was a difficult task.

This changed thanks to the invention of the vacuum-tube rectifier by English physicist John Ambrose Flemming. These tubes, or valves, were subsequently used in  long-distance radios to rectify power, amplitude, and signal strength. Marconi developed the use of vacuum-tubes further as radio detectors. Valves became the standard in radios until the age of transistors came along in the 1950s. So it was that commercial aviation moved forward from Marconi’s Radio-telegraph into the age of Radio-telephony

long-distance radios to rectify power, amplitude, and signal strength. Marconi developed the use of vacuum-tubes further as radio detectors. Valves became the standard in radios until the age of transistors came along in the 1950s. So it was that commercial aviation moved forward from Marconi’s Radio-telegraph into the age of Radio-telephony

Now that radiocommunications in aviation started to use speech, a clear and understandable language was needed to avoid misunderstandings across the airwaves.

The language of the skies

And so it was that in June 1915 the world’s first air-to-ground voice transmission took place over Brooklands, UK with a range of approximately 20 miles. By early 1916, the Marconi Company (England) started producing air-to-ground transmitter/receivers (transceivers).

And so it was that in June 1915 the world’s first air-to-ground voice transmission took place over Brooklands, UK with a range of approximately 20 miles. By early 1916, the Marconi Company (England) started producing air-to-ground transmitter/receivers (transceivers).

Marconi Model 16 Balanced Crystal

Receiver (1916)

In the early days of voice transmissions, aircraft were short-range and this didn’t pose a problem in air-to-ground communications – airmen could speak in their own language as flights didn’t cover long distances and generally were domestic flights. However, as we know, this soon changed. As aircraft manufacturers started building larger, more powerful aircraft, the range of these airplanes became greater, and so the world entered into the era of intercontinental flight. This now posed a great communication problem.

With the advent of intercontinental flights flying from one country to another, this created a language barrier and created problems in communication due to there not being a standard lingua-franca in aviation. This, too, would change.

During World War II, in Britain, the Royal Air Force was divided into several squadrons dotted around the country. It was soon noticed that many pilots were communicating with each other in a strange language, or dialect, unique to that squadron. To the untrained ear, that language was completely “foreign” – if you didn’t know this “language”, it was impossible to understand it – it was English, but not as we know it. This “dialect” used English words, but in phrases that had no grammatical coherence whatsoever. That “language” came to be known as RAF Banter.

During World War II, in Britain, the Royal Air Force was divided into several squadrons dotted around the country. It was soon noticed that many pilots were communicating with each other in a strange language, or dialect, unique to that squadron. To the untrained ear, that language was completely “foreign” – if you didn’t know this “language”, it was impossible to understand it – it was English, but not as we know it. This “dialect” used English words, but in phrases that had no grammatical coherence whatsoever. That “language” came to be known as RAF Banter.

The problem still remained – each squadron had its own Banter. However, it was soon noted that if all the pilots in the RAF spoke the same Banter, they could have an advantage in the air against the German Luftwaffe’s fighters. This proved true during the famous Battle of Britain where German pilots had no idea of what the Brits were communicating to each other… The language of the skies was born, but it needed to mature, it needed refinements.

After the war, many of the RAF’s pilots went on to fly for commercial airlines like Britain’s Imperial Airways. As a result, this strange language was now being used in commercial aviation. The best example of how this Banter was mixed with English is probably the most known word in aviation – Roger. But how could a name become a phrase meaning ‘I understood your last transmission’? That was what made this language so fascinating and unique.

But the language was not yet an international language, so, with the formation of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) on 4 April 1947, in 1951 ICAO established English as the international language to be used in civil aviation. This now meant that pilots and Air Traffic Controllers had to learn English if it wasn’t their mother tongue. They also had to learn all those strange expressions that RAF Banter had introduced… and how to use them correctly. The aim was to have a standard language that avoided any misunderstandings.

But the language was not yet an international language, so, with the formation of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) on 4 April 1947, in 1951 ICAO established English as the international language to be used in civil aviation. This now meant that pilots and Air Traffic Controllers had to learn English if it wasn’t their mother tongue. They also had to learn all those strange expressions that RAF Banter had introduced… and how to use them correctly. The aim was to have a standard language that avoided any misunderstandings.

But Aviation English was still in its early stages and some pilots and controllers were still using their mother tongue between co-nationals… which, unfortunately, still happens today. Added to this was the problem that not all pilots and controllers spoke good English.

A standard had to be set…

Introduction of ICAO Standard Phraseology

On 20 March 1984, Joan Bellec and Fiona Robertson at the Centre for Applied Linguistics of the University de Franche Compte (Besançon, France) organised the first Aviation English Forum, primarily for teachers. The purpose was to, over the years, have this event encompass all areas and aspects of training, testing, and use of English in aviation. This was the birth of a new organisation created with the aim of standardising Aviation English. The name of this organisation came to be known as the International Aviation English Association (IAEA). Today it is known by the name International Civil Aviation English Association (ICAEA).

On 20 March 1984, Joan Bellec and Fiona Robertson at the Centre for Applied Linguistics of the University de Franche Compte (Besançon, France) organised the first Aviation English Forum, primarily for teachers. The purpose was to, over the years, have this event encompass all areas and aspects of training, testing, and use of English in aviation. This was the birth of a new organisation created with the aim of standardising Aviation English. The name of this organisation came to be known as the International Aviation English Association (IAEA). Today it is known by the name International Civil Aviation English Association (ICAEA).

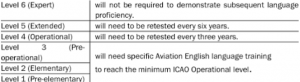

Language Proficiency Requirements (LPR) – ICAO and ICAEA

In the mid 2000s, both ICAO and ICAEA worked together to set a standard in Language Proficiency Requirements for pilots and Air Traffic Controllers. It was time to set minimum standards for the level of English used in aviation. ICAO set about devising a scoring system to set levels of proficiency in Aviation English. These levels went from 1 (the lowest) to 6 (the highest). As well as establishing these levels, ICAO and ICAEA had to set a minimum operational level (where pilots and controllers can carry out their duties), and the period of time that pilots and ATCOs can possess a valid licence before having to retake a test. Also what needed to be implemented was what would be the standard phraseology used, how to deliver training in Aviation English, who was qualified to teach the subject, what requirements were needed to qualify to teach, what was to be taught, how the exams/tests were to be designed and delivered, and how to rate pilots and ATCOs according to their proficiency level.

In the mid 2000s, both ICAO and ICAEA worked together to set a standard in Language Proficiency Requirements for pilots and Air Traffic Controllers. It was time to set minimum standards for the level of English used in aviation. ICAO set about devising a scoring system to set levels of proficiency in Aviation English. These levels went from 1 (the lowest) to 6 (the highest). As well as establishing these levels, ICAO and ICAEA had to set a minimum operational level (where pilots and controllers can carry out their duties), and the period of time that pilots and ATCOs can possess a valid licence before having to retake a test. Also what needed to be implemented was what would be the standard phraseology used, how to deliver training in Aviation English, who was qualified to teach the subject, what requirements were needed to qualify to teach, what was to be taught, how the exams/tests were to be designed and delivered, and how to rate pilots and ATCOs according to their proficiency level.

ICAO doc. 9835 and ICAO circ. 323 – the guidelines in Aviation English

Both ICAO and ICAEA set to work on producing guidelines that would establish a standard in training and testing in Aviation English. The proficiency levels were also set out clearly. For this, two main guidelines were produced – ICAO doc. 9835 and ICAO circ. 323. The minimum Operational Level was set to 4.

ICAO Language Proficiency

ICAO Language Proficiency

Levels and retesting

In 2004 ICAO produced the first edition of Document 9835 – Manual on the Implementation of ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements. This 150-page document has the purpose of providing comprehensive information on a range of aspects related to language proficiency training and testing, in order to support States’ efforts to comply with the strengthened provisions for language proficiency. It was important to set out these requirements so that standards could be applied internationally and all pilots and Air Traffic Controllers would receive the same training in Standard Phraseology, and all would receive the same exam/test type and level scoring.

In 2004 ICAO produced the first edition of Document 9835 – Manual on the Implementation of ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements. This 150-page document has the purpose of providing comprehensive information on a range of aspects related to language proficiency training and testing, in order to support States’ efforts to comply with the strengthened provisions for language proficiency. It was important to set out these requirements so that standards could be applied internationally and all pilots and Air Traffic Controllers would receive the same training in Standard Phraseology, and all would receive the same exam/test type and level scoring.

In 2009 ICAEA and ICAO co-wrote Circular 323 – Guidelines for Aviation English Training Programmes. The purpose of this 80-page circular was to set out guidance and best practices by which Aviation English training programs can be designed, delivered, staffed, managed and assessed for appropriately, efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

In 2009 ICAEA and ICAO co-wrote Circular 323 – Guidelines for Aviation English Training Programmes. The purpose of this 80-page circular was to set out guidance and best practices by which Aviation English training programs can be designed, delivered, staffed, managed and assessed for appropriately, efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

These two “manuals” would set the criteria by which Aviation English would be designed, delivered, and by whom. They also set out how to test and assess the pilot or Air Traffic Controller.

They were to determine what language, pronunciation and phraseology were to be used internationally in aviation. They were created so that aviation safety around the world would be maintained, and that misunderstandings in pilot-controller communications would be eradicated.

However, the most important aspect of these two documents is to prevent English language schools around the world to offer Aviation English courses by unqualified “trainers”. All English language schools and aviation training centres are under obligation to fully comply with the regulations and requirements set out within these two documents.

What do pilots, Air Traffic Controllers and Cabin Crew say?

Having several years of experience training crew for two major European airlines, and Air Traffic Controllers, in Aviation English with, I’m pleased to say, 100% success rate in exam passes, in addition to having trained Cabin Crew in English for Cabin Crew, I know what problems these airmen and women face in the day-to-day challenges they encounter in their jobs with the use of English in aviation. On some recent flights I had this year, I was able to speak to pilots and Cabin Crew of one particular European airline about these challenges. All of the ones I spoke with said that finding a good training centre or school that would give them the necessary training to pass their exam was difficult. Often they would find that they didn’t get the course content they expected and that the courses were delivered by English language teachers who were unfamiliar with aviation. Many failed the exam as a result and had to spend more money on preparing for and re-taking the test. Air Traffic Controllers complained that there are very, in fact, too few courses designed to help them prepare for their exam. All complained that, even though several years have passed since ICAO doc. 9835 and circ. 323 were published, there are still problems with training in Aviation English, and that the standards in issuing the correct ICAO Language Proficiency Level were poor in some countries.

Having several years of experience training crew for two major European airlines, and Air Traffic Controllers, in Aviation English with, I’m pleased to say, 100% success rate in exam passes, in addition to having trained Cabin Crew in English for Cabin Crew, I know what problems these airmen and women face in the day-to-day challenges they encounter in their jobs with the use of English in aviation. On some recent flights I had this year, I was able to speak to pilots and Cabin Crew of one particular European airline about these challenges. All of the ones I spoke with said that finding a good training centre or school that would give them the necessary training to pass their exam was difficult. Often they would find that they didn’t get the course content they expected and that the courses were delivered by English language teachers who were unfamiliar with aviation. Many failed the exam as a result and had to spend more money on preparing for and re-taking the test. Air Traffic Controllers complained that there are very, in fact, too few courses designed to help them prepare for their exam. All complained that, even though several years have passed since ICAO doc. 9835 and circ. 323 were published, there are still problems with training in Aviation English, and that the standards in issuing the correct ICAO Language Proficiency Level were poor in some countries.

Continuing improvements in effective Aviation English training

The correct interpretation, understanding and implementation of ICAO doc. 9835 and

circ. 323 should lead to a better, more effective structure in training students in language proficiency in Aviation English. Looking at improving courses with the use of technology and interactive activities which place pilots, ATCOs, and Cabin Crew in situations which involve standard and non-standard procedures, could be the solution to better training and higher first-time pass rates in the all-important exams/tests that keep our crews in the air, and in the tower and ATC centres.

If you’re a pilot, an Air Traffic Controller, or Cabin Crew, choose where you go to train carefully. Enquire about who is going to train you, what is their background and knowledge of aviation and the course content. Ask if the centre or school complies with current ICAO and ICAEA standards… and don’t forget to ask what the success rate in exam passes is for Aviation English students.

If you are an English language school or aviation training centre and are currently not delivering Aviation English courses but would like to, please familiarise yourselves fully with ICAO doc. 9835 and circ. 323. It’s not impossible to teach Aviation English, but it requires time to train teachers with zero subject matter in aviation to be qualified to teach the courses… 3 years in total. If this is an area of courses you would like to enter into and need teacher training, look for schools who have a qualified instructor able to train your teachers in a very different and unique way of teaching to General English language courses, or General English exam preparation and IELTS courses. Many wrongly say that Aviation English is ‘just another English for Specific Purposes‘ course and that any teacher can pick up a course book and teach – this is just something that the publishers of Aviation English coursebooks write in the Teacher’s Book. This is very different to what is set out in the two ICAO documents. Remember that these requirements were compiled with aviation safety in mind – the safety of millions of people flying year in, year out.